Study Shows Limits of Ozonated Water as Sanitizer in Raw Veggie Processing

Ozone water reduces cross-contamination in food-processing sanitation equipment

By John Lovett – Nov. 29, 2023

(Editor’s note: This version SUBS graf 2 reflecting a change in wording on percentage of sick pet visits.)

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — Ozone can be a powerful and safe sanitizer when infused in water for food processing. However, in a recent Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station study looking at its use in raw pet food processing, scientists found that ozonated water sanitation’s effectiveness is variable depending on how it is applied, and on what foods.

According to the study published in the November edition of the Journal of Food Protection, it has been reported that up to 35 percent of sick pet visits to veterinary clinics are due to salmonellosis, a disease caused by the foodborne pathogen Salmonella, likely transmitted through contaminated raw pet food. The study also states that some human cases of salmonellosis have been linked to contaminated raw pet food.

Ozone, the same gas in the stratosphere protecting Earth from ultraviolet radiation, comprises three oxygen molecules. While harmful to humans and animals if airborne, when dissolved into water, it is a safe sanitizer that can nearly eliminate bacteria without leaving any harmful residue, said Kristen Gibson, lead researcher on the study and professor of food safety and microbiology for the experiment station, the research arm of the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture.

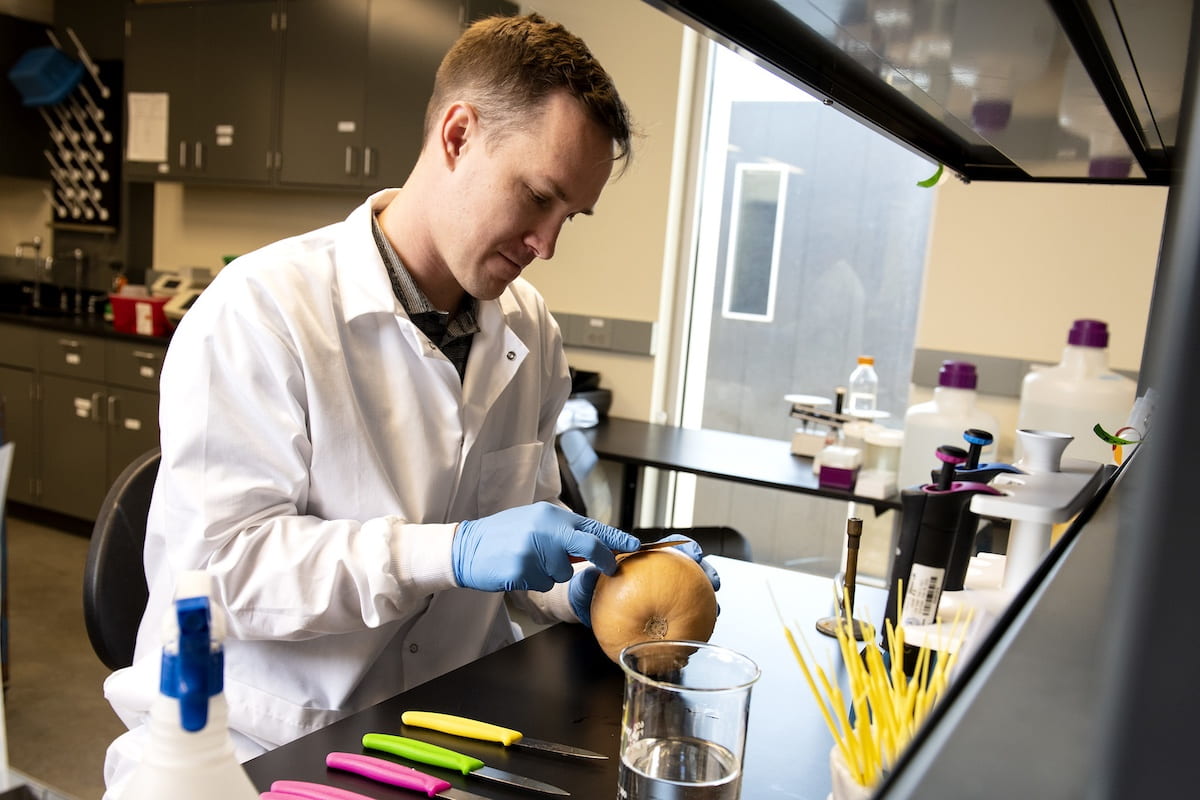

The experiment station study aimed to measure the ability of ozonated water — also called aqueous ozone — to control foodborne pathogens on raw vegetables commonly used in raw-meat-based pet foods. Researchers evaluated carrots, sweet potatoes and butternut squash.

Listeria monocytogenes, the cause of listeriosis, was another pathogen of concern for the study. The food science department conducted the study as a third-party evaluation for a raw pet food maker in Arkansas.

“What we didn’t know was the efficacy of the technology against pathogens on the root and tuber vegetables we explored,” Gibson said. “Ozone has been shown to be effective against gram-positive and gram-negative microorganisms, but the variables influencing the efficacy are of interest.”

Listeria remains a stubborn foe for raw pet food makers. The gram-positive bacterium has been shown to resist harsh processing conditions such as high and cold temperatures and modified atmospheres. Cooking temperatures kill the pathogen, but food processors are focused on limiting thermal activity to preserve flavors. Even with high-pressure processing and frozen storage, raw pet food makers have been unable to reduce Listeria as much as other harmful foodborne pathogens like Salmonella and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, also known as STEC.

E. coli are a diverse group of bacteria that normally live in the intestines of humans and animals. Although most strains of these bacteria are harmless, some produce toxins like Shiga toxin that can cause severe illness. Salmonella and STEC can cause gastroenteritis in humans and pets, with stomach cramps and bloody diarrhea as symptoms. Complications from STEC include chronic aftereffects, such as kidney failure.

Reducing cross-contamination

Gibson’s team used two methods to apply aqueous ozone — spray-washing through a nozzle at 15.5 pounds per square inch of pressure and batch-washing, which submerges the vegetables into a tank of aqueous ozone.

A secondary goal was to confirm aqueous ozone’s ability to reduce cross-contamination in recirculating water tanks.

Gibson, who is also director of the Arkansas Center for Food Safety, said that while neither spray-wash nor batch-wash tests with ozonated water reached the level of pathogen reduction that high-pressure processing provides, the study confirmed best-practice strategies for processors of any fruit and vegetable using recirculating water systems. High-pressure processing calls for isostatic pressure — pressure applied from all directions — transmitted by cold water up to 87,000 psi and held for a few minutes. The process achieves what is equivalent to pasteurization without using heat.

“If you’re using water at all in the process, especially for moving produce through a general wash, aqueous ozone would be quite good to mitigate cross-contamination,” Gibson said.

For example, the water used to clean vegetables in a recirculating water system could harbor foodborne pathogens from a highly contaminated batch and possibly cross-contaminate a clean batch. The ozone treatment prevented microbial cross-contamination of sanitation equipment and nearby surfaces.

“The sanitizer would be quite good for that reason, for keeping the system clean and reducing the microbial risk that could appear once bacteria are dislodged from the produce,” Gibson said. “When the aqueous ozone was present, it kept the level of bacteria in that system low, which is what you want. You don’t want the microorganisms to start accumulating within the system or on the surfaces. So, that was a positive aspect of the study and reiterated much of what we know about how water can be a great way to spread contamination.”

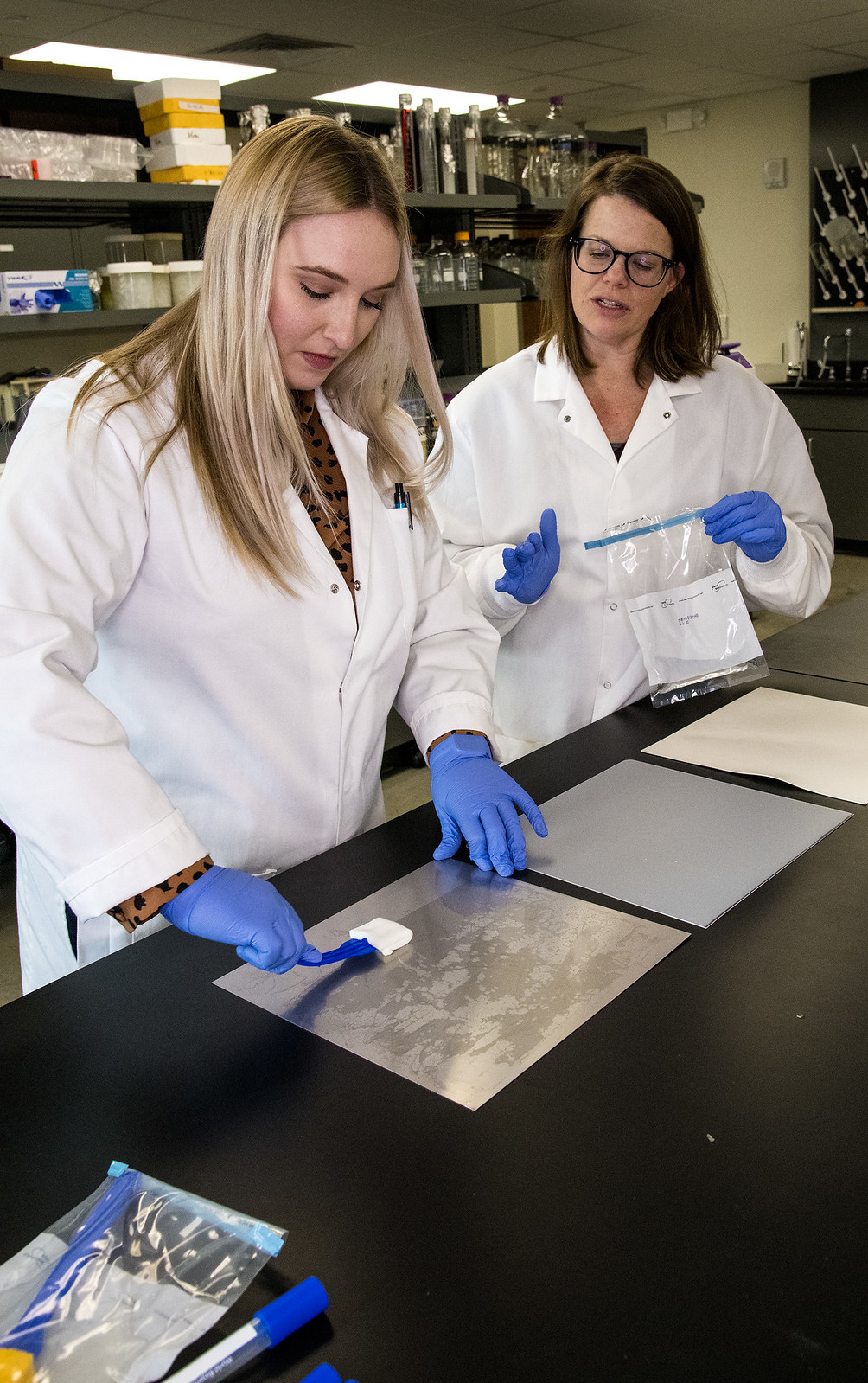

LAB TESTS — Sarah Jones, left, and Kristen Gibson investigate the efficiency of food pathogen monitoring tools in the Don Tyson Center for Agricultural Research. (U of A System Division of Agriculture photo)

Rough vs. smooth surfaces

Gibson said studies analyzing the efficacy of aqueous ozone against pathogens on vegetables with rough surfaces like root vegetables, tubers, radishes and winter squash are limited. She added that vegetables with rough surfaces have a higher chance of harboring pathogens, and there is a higher chance of root vegetables being contaminated due to the potential colonization of pathogenic bacteria within the root zone.

The experiment station study tested carrots as a root vegetable and sweet potatoes as a tuber. With skin roughness and aqueous ozone efficacy in mind, Gibson added the smooth-skinned butternut squash to the study for comparison. This vegetable is also commonly found in raw pet food.

The 15.5 psi spray-wash treatment used in the study was more effective at reducing the pathogens on butternut squash, nearly to industry standards. Yet still, the carrots and sweet potatoes could not be sanitized to industry standards with either treatment.

The study used a concentration of 5 parts per million ozone in water with exposure times of 20 seconds and 60 seconds. The vegetables were kept frozen until exposed to the ozonated water. Gibson said the water pressure and friction from the spray-wash treatment may have assisted in dislodging the bacteria from the outer surface of the vegetables, allowing for inactivation by ozonated water.

Based on the experiment station study results, Gibson and her co-authors concluded that batch-washing with aqueous ozone at five parts per million for 60 seconds was the same as washing the vegetables in plain water. Higher ozone concentrations in water, with longer exposure times, have been shown to damage the appearance of physiological properties of carrots, the study noted.

The study’s co-authors included Sahaana Chandran, Christopher A. Baker, Allyson N. Hamilton, Gayatri R. Dhulappanavar, and Sarah L. Jones. Chandran, Hamilton and Dhulappanavar are Ph.D. students in the food science department. Jones received her doctorate and now works for Newly Weds Foods. Baker was a post-doctoral researcher during the study and now works for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

The research was supported in part by Instinct® Pet Food, Recycled Hydro Solutions, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Mention of these companies does not represent a product endorsement. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has also not formally reviewed the study. It should not be construed to represent agency determination or policy.

To learn more about Division of Agriculture research, visit the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station website: https://aaes.uada.edu. Follow us on 𝕏 at @ArkAgResearch and Instagram at @ArkAgResearch.

To learn about Extension Programs in Arkansas, contact your local Cooperative Extension Service agent or visit https://uaex.uada.edu/. Follow us on 𝕏 at @AR_Extension.

To learn more about the Division of Agriculture, visit https://uada.edu/. Follow us on 𝕏 at @AgInArk.

About the Division of Agriculture

The University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture’s mission is to strengthen agriculture, communities, and families by connecting trusted research to the adoption of best practices. Through the Agricultural Experiment Station and the Cooperative Extension Service, the Division of Agriculture conducts research and extension work within the nation’s historic land grant education system.

The Division of Agriculture is one of 20 entities within the University of Arkansas System. It has offices in all 75 counties in Arkansas and faculty on five system campuses.

The University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture offers all its Extension and Research programs and services without regard to race, color, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, national origin, religion, age, disability, marital or veteran status, genetic information, or any other legally protected status, and is an Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer.

LAB TESTS — Sarah Jones, left, and Kristen Gibson investigate the efficiency of food pathogen monitoring tools in the Don Tyson Center for Agricultural Research. (U of A System Division of Agriculture photo)